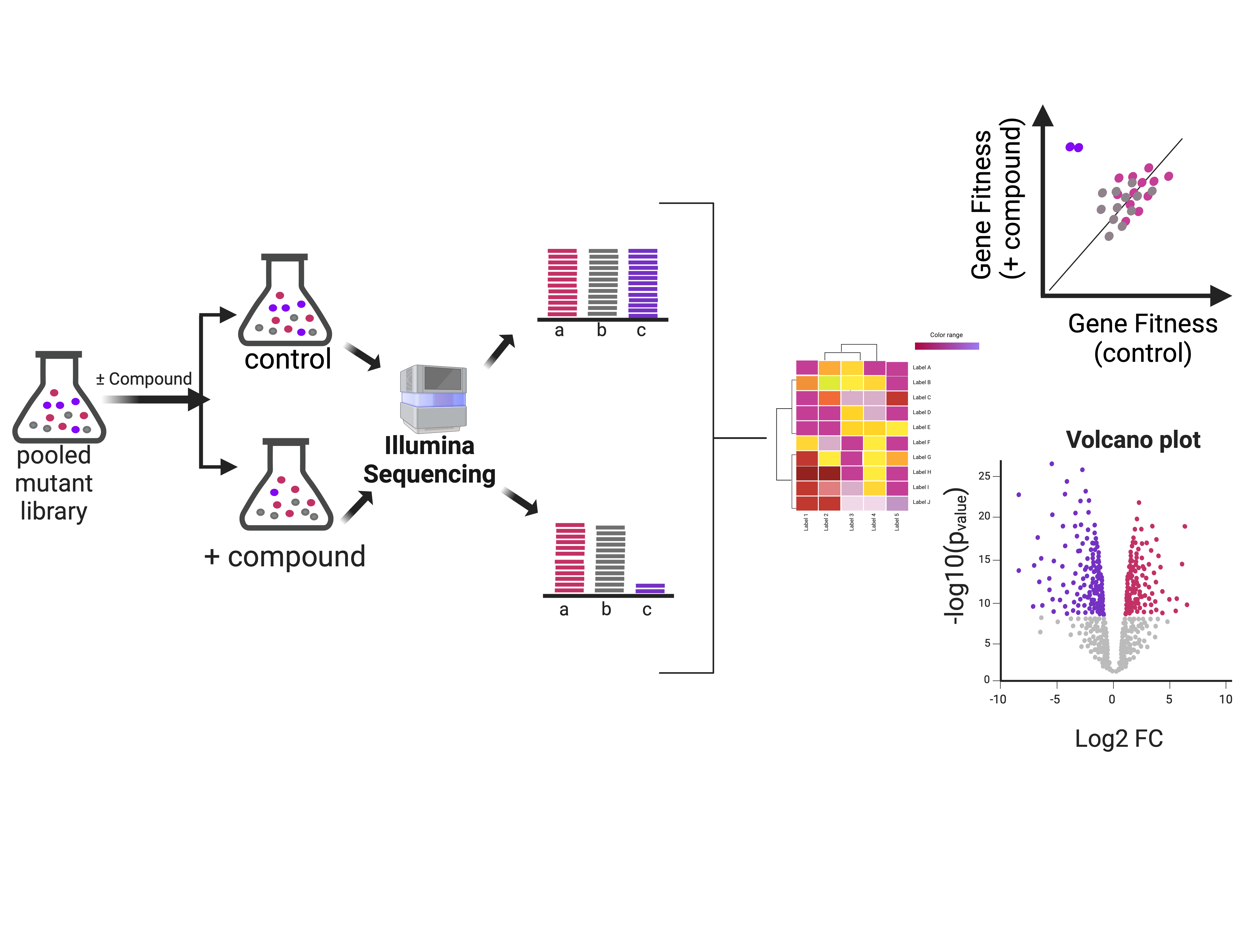

The clinical arsenal of antibiotics is losing effectiveness due to the spread of resistance. To counter this, our lab aims to understand how current antibiotics work so we can exploit synergistic mechanisms to make them more effective. We are also interested in the mechanism of action of novel compounds and how they work, which is critical to further rational drug optimization approaches. Chemogenomics, the genomic response of the cell to chemical compounds is a powerful tool to answer these questions. To that end, we build DNA barcoded genomic libraries, expose them to the drugs under investigation and characterize the genomic response by tracking mutant relative abundance by sequencing the unique barcodes.

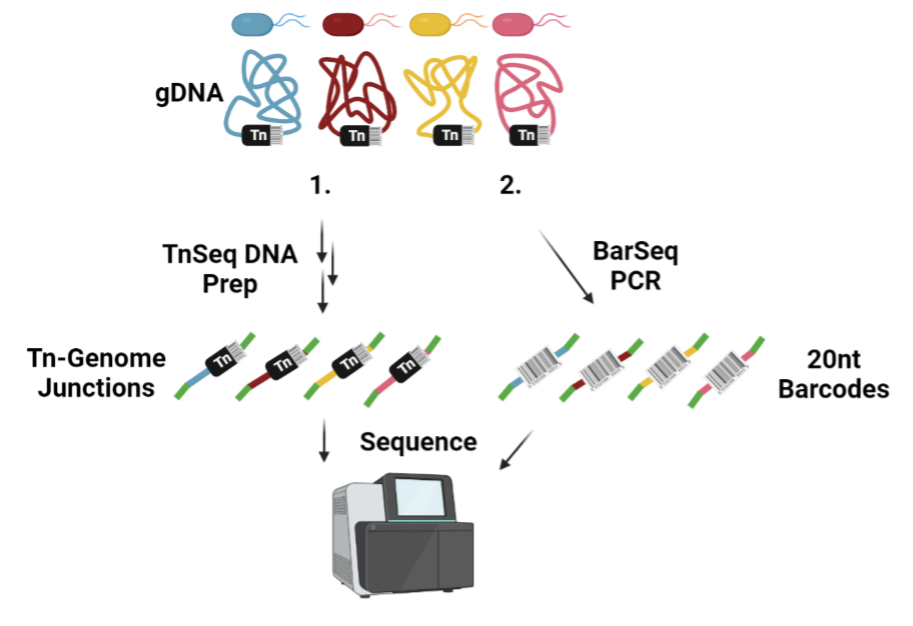

Our platform harnesses the power of next-generation sequencing with high-throughput target inquiry. Using barcoded transposon mutagenesis (BarSeq) to systematically inactivate every non-essential gene in the genome, we gain a genome-wide perspective on how each gene contributes to resistance or susceptibility. Hundreds of thousands of mutants are grown in a pool with a small molecule. Illumina sequencing is then used to determine the abundance of each mutant. Unique DNA barcodes identify each mutant, greatly increasing the throughput of our platform.

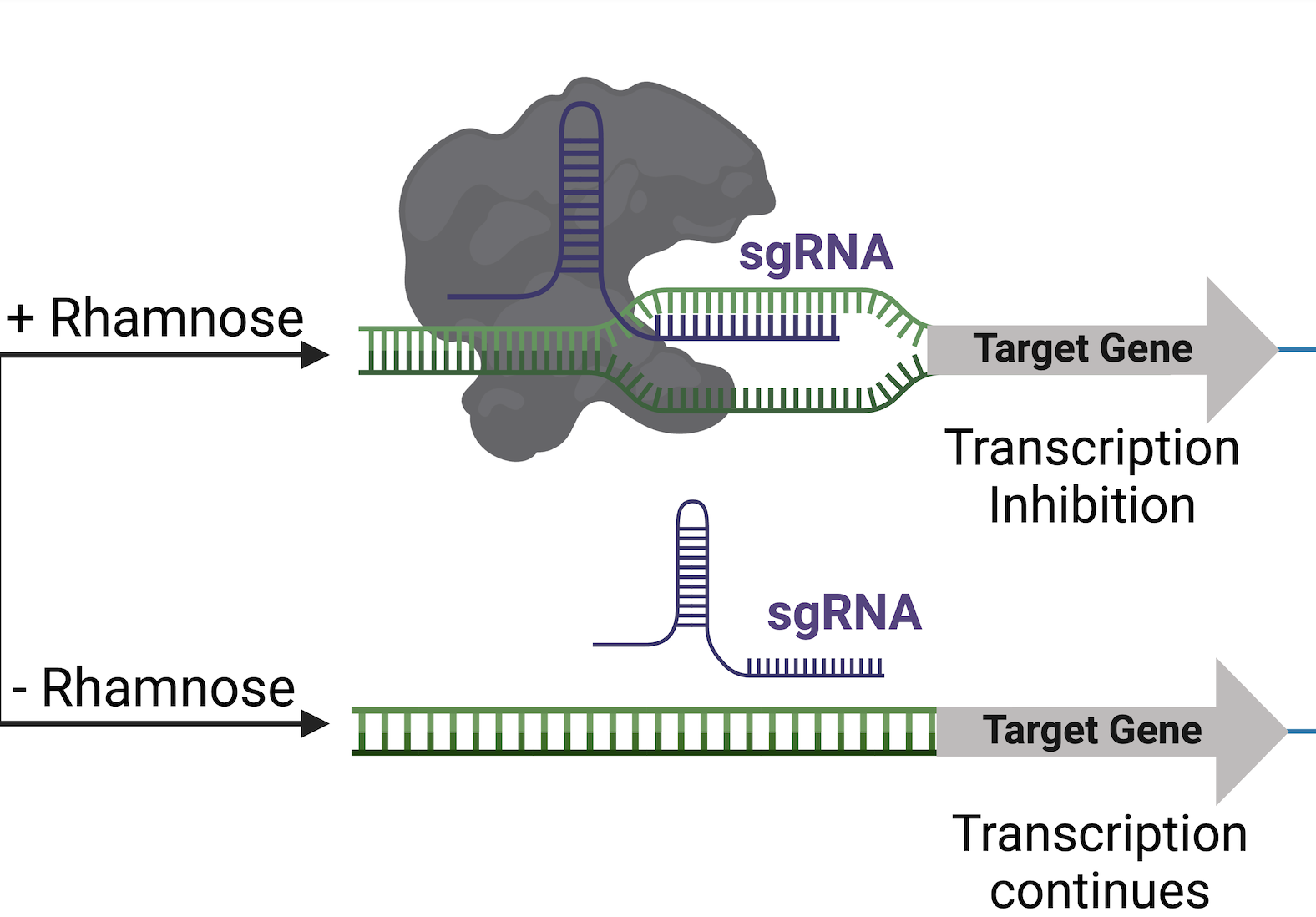

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) is an ideal tool for creating mutant libraries in essential genes. CRISPRI allows inducible repression of essential gene expression in bacteria, by utilizing a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) to form a complex that binds to target DNA and sterically blocks transcription. Our knockdown libraries are bulit with CRISPRi technology and contain mutants in essential genes, which usually code for targets of antibiotics. We expect that chemogenetic profiles of essential gene knockdowns will better predict antibiotic activity and mode of action (MOA) of novel compounds, accelerating antibiotic discovery.

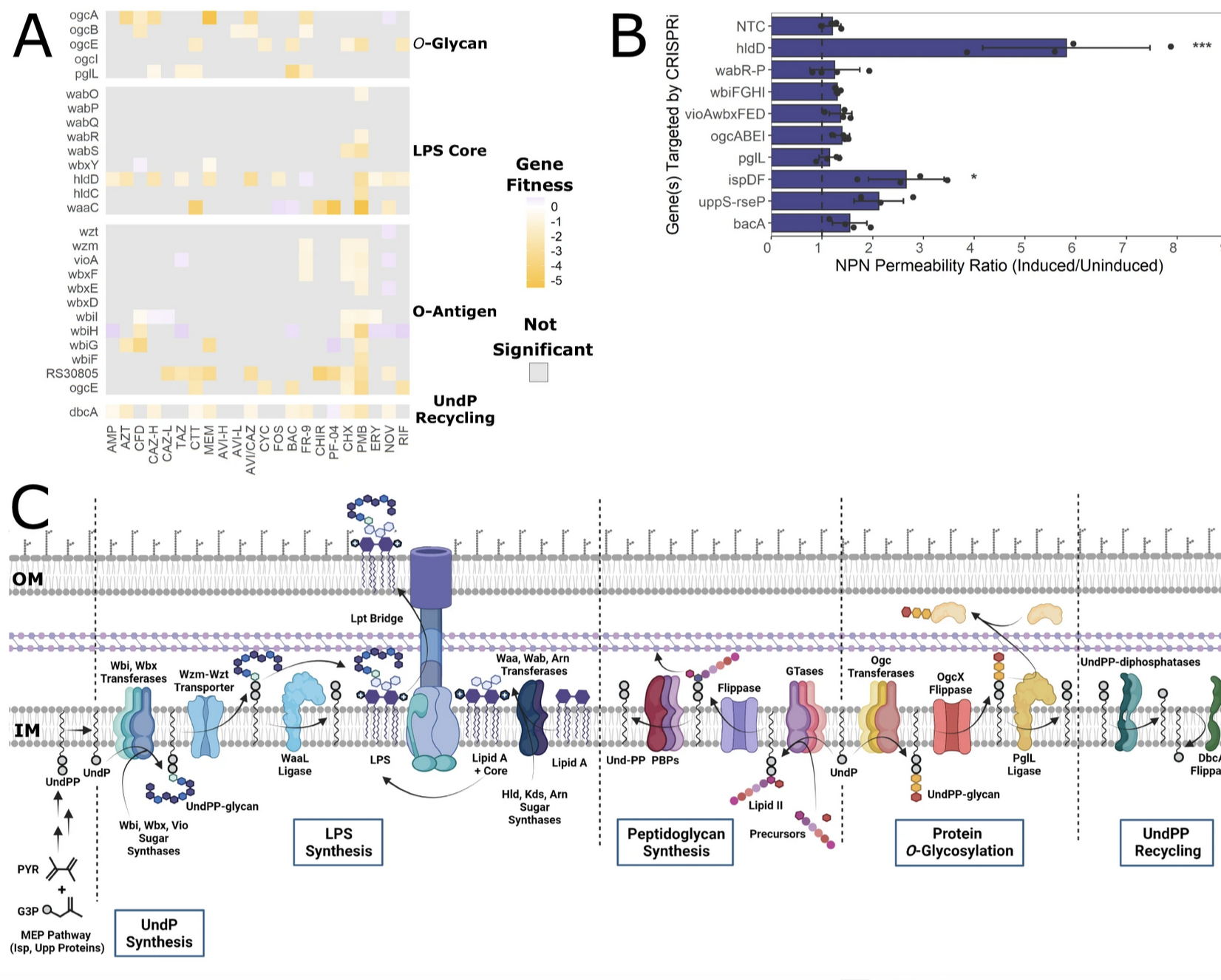

To characterize antimicrobial mechanisms of action, we exposed the mutant libraries to the compounds, and the relative mutant fitness response was recorded by counting the abundance of sequenced barcodes for each strain. A change in a specific barcode count relative to the non-antibiotic control reports on compound-gene interactions. BarSeq uncovered that, when undecaprenyl phosphate turnover was disrupted, B. cenocepacia became more susceptible to beta-lactams. This finding highlighted the many cell envelope functions that share the common intermediate undecaprenyl phosphate and allowed us to explore antibiotic combinations to extend beta-lactam utility (Hogan AM et al., 2023, Nature Communications 14:4815).

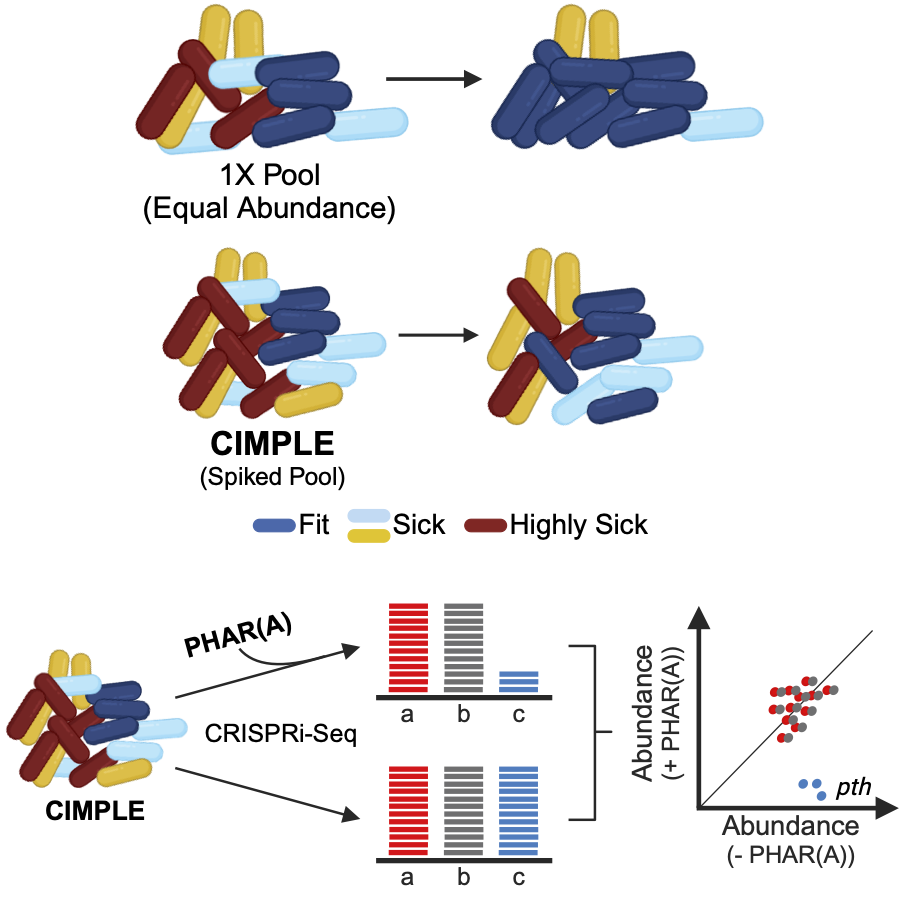

Targeting essential genes with BarSeq is not possible because mutants of essential genes are not viable. We then used CRISPR interference (CRISPRi). Similarly to Bar-seq, CRISPRi-seq uses barcodes (the gRNA sequences) to track mutant growth response to different conditions. Aiming to cover the B. cenocepacia essential genome, we built an ordered, pooled library of CRISPRi mutants (CRISPRi–mediated pooled library of essential genes, CIMPLE) and applied CRISPRi-seq to track mutant response to antibiotic molecules (CIMPLE-seq). Using this method we unraveled a new drug-target interaction, PHAR(A) targets the peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (Rahman, A.S.M.Z et al., 2024 Cell Reports).